Long term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of acute coronary events: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis in 11 European cohorts from the ESCAPE Project

BMJ 2014; 348 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7412 (Published 21 January 2014) Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:f7412

All rapid responses

Rapid responses are electronic comments to the editor. They enable our users to debate issues raised in articles published on bmj.com. A rapid response is first posted online. If you need the URL (web address) of an individual response, simply click on the response headline and copy the URL from the browser window. A proportion of responses will, after editing, be published online and in the print journal as letters, which are indexed in PubMed. Rapid responses are not indexed in PubMed and they are not journal articles. The BMJ reserves the right to remove responses which are being wilfully misrepresented as published articles or when it is brought to our attention that a response spreads misinformation.

From March 2022, the word limit for rapid responses will be 600 words not including references and author details. We will no longer post responses that exceed this limit.

The word limit for letters selected from posted responses remains 300 words.

Dear editor,

In recent articles published in BMJ [1-4] a problem of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) genesis was discussed. Certainly, environmental factors, lipid excess in nutrition, obesity, renal disease and other traditional risk factors play an important role in development of the CVD. But we believe that molecular genetic defects, particularly mitochondrial genome mutations, might be significant in pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases [5].

To detect the spectrum of mitochondrial mutations in individuals, we used a high efficiency pyrosequencing of the whole mitochondrial genome.

Whole blood samples were taken from 77 subjects, among them 45 patients had carotid atherosclerosis assessed by ultrasonography [6]; and 32 subjects had no atherosclerotic lesions. DNA was extracted by a phenol chloroform method. Afterwards an enriching of mitochondrial DNA was performed using Qiagen™ REPLI-g Mitochondrial Kit. To carry out a high efficiency pyrosequencing of the whole mitochondrial genome, a system Roche 454 GS Junior Titanium (Roche, USA) was used.

An analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequence was performed using GS Reference Mapper program. The Cambridge standard sequence NC_012920.1 was used for mapping human mitochondrial genome [7]. Statistical data processing was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics v.21.0.

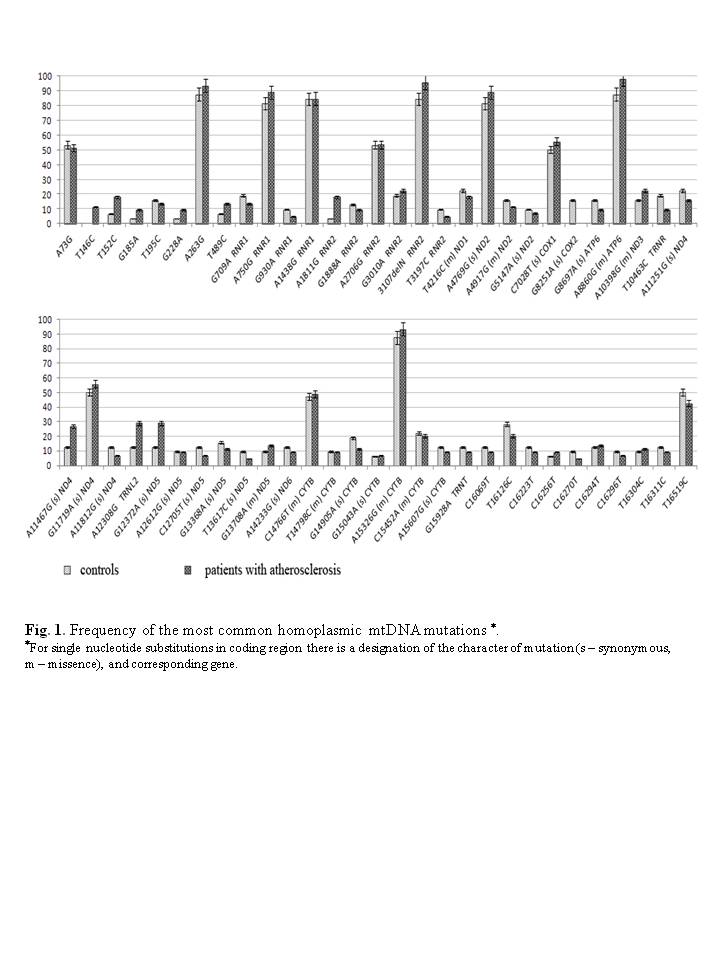

A whole genome pyrosequencing gave an opportunity to detect 58 homoplasmic mitochondrial genome mutations in the investigated samples. The frequency of mutations T152C, G185A, G228A, A263G, 3107delN, T489C, A750G, A1811G, A4769G, C7028T , A8860G, A10398G, A11467G, A11719G, A12308G, G12372A and A15326G turned to be significantly higher in patients with atherosclerosis than in healthy study participants. At the same time mitochondrial mutations T4216C, A4917G, G8697A, T10463C, A11251G, A11812G, A12705T, A13368A, A13617C, G14905A, A15607G, G15928A, T16069T, T16126C, C16223T, C16296T, T16311C and T16519C prevailed in healthy individuals (Figure 1).

In addition, nine heteroplasmic mutations associated with atherosclerosis were found, namely: 576insC, 8516insA, 8516insC, 8528insA, G9477A, 8930insG, 10958insC, 13047insC и 13050insC.

It should be noted that 29% homoplasmic and 33% heteroplasmic proatherogenic mutations of mitochondrial genome belong to genes coding NADH dehydrogenase subunits; 18% homoplasmic atherogenic mutations are localized in genes coding rRNA subunits and 44% heteroplasmic single-nucleotide insertions are localized in genes coding ATP synthetase subunits. It can be assumed that the defects in NADH dehydrogenase, ATP synthetase and mitochondrial ribosomes may participate in realization of the mechanisms of atherogenesis.

Previously, using pyrosequencer PSQTMHS96MA (Biotage, Sweden) we have found 11 heteroplasmic mutations associated with atherosclerosis: 652delG, A1555G, C3256T, T3336C, C5178A, 652insG , G12315A, G14459A, G13513A, G14846A and G15059A [8-10]. In the present study we did not detect the above mutations, possibly due to the fact that an intermediate stage of the whole mitochondrial genome PCR is not necessary for studying separate mutations with a pyrosequenator PSQTMHS96MA. Thus, it can desensitize Roche technology. However, this disadvantage is highly compensated by a high number of mutations associated with atherosclerosis, which can be detected during whole genome pyrosequencing.

This study was supported by the Russian Ministry of Education and Science.

References

1. Long term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of acute coronary

events: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis in 11 European cohorts from the ESCAPE Project. Cesaroni G, Forastiere F, Stafoggia M, Andersen ZJ, Badaloni C, Beelen R, Caracciolo B, de Faire U, Erbel R, Eriksen KT, Fratiglioni L, Galassi C, Hampel R, Heier M, Hennig F, Hilding A, Hoffmann B, Houthuijs D, Jöckel KH, Korek M, Lanki T, Leander K, Magnusson PK, Migliore E, Ostenson CG, Overvad K, Pedersen NL, J JP, Penell J, Pershagen G, Pyko A, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Ranzi A, Ricceri F, Sacerdote C, Salomaa V, Swart W, Turunen AW, Vineis P, Weinmayr G, Wolf K, de Hoogh K, Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Peters A.BMJ. 2014 Jan 21;348:f7412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7412.

2. Mann J, McLean R, Te Morenga L. Evidence favours an association

between saturated fat intake and coronary heart disease. BMJ. 2013 Nov 19;347:f6851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6851

3. Kmietowicz Z. Obesity increases heart disease risk in absence of metabolic

risk factors. BMJ. 2013 Nov 12;347:f6797. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6797

4. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration, Ninomiya T,

Perkovic V, Turnbull F, Neal B, Barzi F, Cass A, Baigent C, Chalmers J, Li N, Woodward M, MacMahon S. Blood pressure lowering and major cardiovascular events in people with and without chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013 Oct 3;347:f5680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5680»

5. Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in human evolution anddisease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91(19 (September)):8739–46. Review.

6. Miasoedova VA, Kirichenko TV, Orekhova VA, Sobenin IA,

Mukhamedova NM, Martirosian DM, Karagodin VP, Orekhov AN. Study of intima-medial thickness (IMT) of the carotid arteries as an indicator of natural atherosclerosis progress in Moscow population. Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter 2012 Jul-Sep;(3):104-8. Russian.

7. Homo sapiens mitochondrion, complete genome. NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_012920.1. URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_012920 (last accessed date: 15.12.2013).

8. Sazonova M, Budnikov E, Khasanova Z, Sobenin I, Postnov A, Orekhov A. Studies of the human aortic intima by a direct quantitative assay of mutant alleles in the mitochondrial genome. Atherosclerosis. 2009, 204(1):184-190. (Epub 2009 Sep 4).

9. Sobenin IA, Sazonova MA, Postnov AY, Bobryshev YV, Orekhov AN. Changes of mitochondria in atherosclerosis: Possible determinant in the pathogenesis of the disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013 Jan 25. doi:pii: S0021-9150(13)00041-5. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.006. [Epub ahead of print].

10. Sobenin IA, Sazonova MA, Postnov AY, Salonen JT, Bobryshev YV, Orekhov AN. Association of mitochondrial genetic variation with carotid atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2013 Jul 9;8(7):e68070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068070. Print 2013.

Competing interests: No competing interests

What about the UK

I am grateful to Mr Quentin Bush (rapid response, 23 Jan) for stimulating me to read the paper. The paper, together with Mr Bush's commentary raises a few awkward questions:

1. Did the authors not try to enlist collaboration of BRITISH cardiac epidemiologists?

2. On the assumption that the fuel used by US airlines flying to, or via, British airports use the same type of fuel as our own (formerly) flag-carrier, will the minister for Public Health here in England issue a public statement, assuring the residents of houses under the flight paths, that their health is safe in her hands?

3. Are there air pollution monitoring units, capable of monitoring the pollutants (referred to in the article and Mr Bush's response) under the flight paths of Heathrow? If so, do they report to the local Director of Public Health? And to to the Medical Adviser of the Mayor of London?

4. Has Public Health England ( a new-born babe) any plans to take an active role in this matter?

Competing interests: No competing interests

The UK BMJ announces on UK television (22/01/2014) the causes of heart attacks, angina and other serious life threatening diseases.

I note the BMJ blame exhaust emissions from vehicles but what they fail to mention are the pollutants from American based aircraft.

FACT

US Patent 5,003,186 Aluminium Oxide in Jet Fuel. This is one of the main causes of death to animals, fish, birds and then the 'soft kill' to humans by cardiovascular morbidity, kidney failure, liver disease, brain deterioration, Alzheimer's. Need I say more.

http://chemtrails.cc/docs/welsbach-seeding-patent.pdf

There is much about this published on the internet, it is truthful, not a conspiracy any longer.

I doubt I will receive a reply, I never do but the truth is hard to acknowledge. It is time to look at the BIGGER world-wide picture.

Quentin Bush.

Competing interests: No competing interests

Re: Long term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of acute coronary events: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis in 11 European cohorts from the ESCAPE Project

We read the paper by Cesaroni et al. with interest (1), and are encouraged by this addition to the evidence base.

It seems counter-intuitive that larger particles of smoke, dust, and dirt (PM10) are significantly associated with coronary events, but smaller toxic organic compounds and heavy metals (PM2.5) are not. However, this was a multi-centre cohort study including a meta-analysis of its eleven cohorts, and must be considered as part of the wider evidence base.

A systematic review in 2009 by Bhaskaran et al. identified 26 studies with Myocardial Infarction as an outcome and air pollution as a risk factor (2). Only 7 studies were long-term studies and the authors concluded that there was some evidence that PM2.5, PM10, and NO2 were associated with detrimental cardiovascular outcomes, but more studies were needed. A 2006 analysis by Pope et al. provides evidence that long-term exposure to PM2.5 is an important risk factor for cause-specific cardiovascular mortality (3). A study by Miller et al. in 2007 followed over 65800 women in 36 US metropolitan areas for 6 years. They found that each increase of 10 μg/m3 in PM2.5 was associated with an increased Odds Ratio of 1.24 (95% CI 1.09-1.41) for the onset of a first cardiovascular event (4).

There are still questions regarding the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. There are a few long-term studies and this paper contributes to the limited evidence base. Studies presently focus on PM10 and PM2.5, with a gap in the evidence base regarding ultrafine particulate matter (PM0.1).

The EU presently sets an annual concentration limit at 25 µg/m3 for PM2.5 and at 40 µg/m3 for PM10 (5), while in the US, the annual concentration limit is 12 µg/m3 for PM2.5 and there is no annual concentration limit for PM10 (6). In order to ensure consistent guidance, it is important to understand better the role of air pollution and particulate matter on coronary events in particular and health in general. Therefore a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of all available data, such as a Cochrane review, is recommended to inform further guidance on air quality standards.

References

1. Cesaroni, Giulia, et al. "Long term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of acute coronary events: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis in 11 European cohorts from the ESCAPE Project." BMJ: British Medical Journal 348 (2013).

2. Bhaskaran, Krishnan, et al. "Effects of air pollution on the incidence of myocardial infarction." Heart 95.21 (2009): 1746-1759.

3. Pope, C. Arden, et al. "Cardiovascular Mortality and Long-Term Exposure to particulate Air Pollution Epidemiological Evidence of General Pathophysiological Pathways of Disease." Circulation 109.1 (2004): 71-77.

4. Miller, Kristin A., et al. "Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women." New England Journal of Medicine 356.5 (2007): 447-458.

5. European Commission. 2014. Air Quality Standards. (online) Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/air/quality/standards.htm (Accessed:5 Feb 2014)

6. Esworthy R. 2013. Air Quality: EPA’s 2013 Changes to the Particulate Matter (PM) Standard. (online) Available at:

http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42934.pdf (Accessed:5 Feb 2014)

Competing interests: No competing interests