Waiting lists: the return of a chronic condition?

BMJ 2023; 380 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p20 (Published 11 January 2023) Cite this as: BMJ 2023;380:p20- John Appleby, director of research and chief economist

- john.appleby{at}nuffieldtrust.org.uk

Elective treatment waiting lists in the NHS in England have reached a record high of 7.1 million people, show the latest official data from NHS England, for September 2022 (fig 1).1 This continues a trend—accelerated by the covid-19 pandemic but evident for years 2—that has seen lists more than triple in size since 2009, when the number was 2.3 million.1

No of patients on elective care waiting list (NHS in England)1

The length of the queue to get treatment would be much less of a concern if it moved quickly. The problem is that it doesn’t. The target is for no more than 8% of patients waiting for a bed in hospital to wait more than 18 weeks from a GP’s referral to treatment; last October just under 40% were still waiting longer than this (fig 2). In February 2020 just 1613 people were still waiting after more than a year; now around 411 000 are.1 From April 2021 worsening waiting times have prompted official statistics to start recording waits of over 18 months and over two years.

Percentage of patients waiting longer than 18 weeks from GP referral to hospital treatment (NHS in England)1

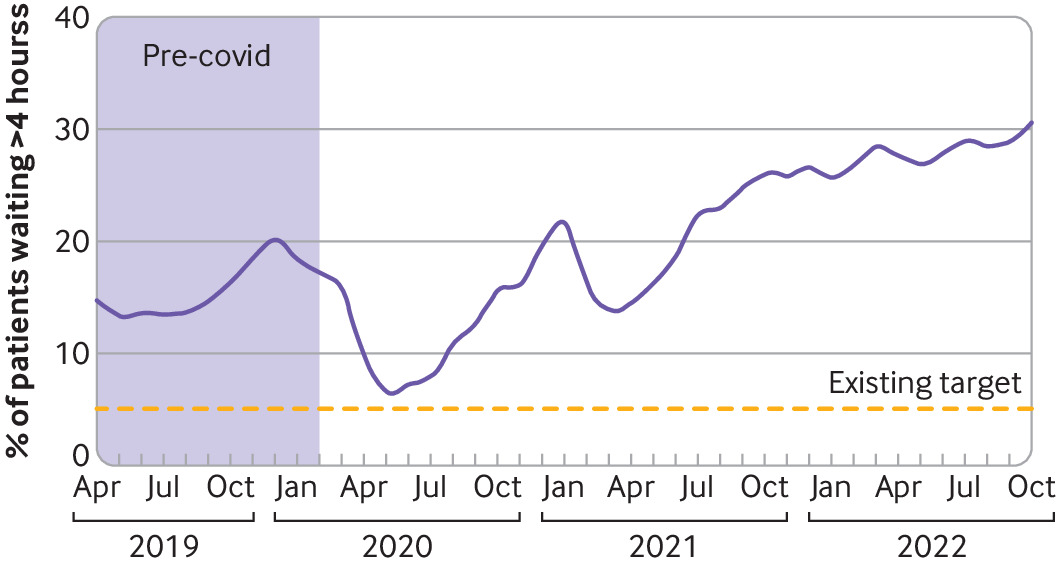

It’s not just elective care that’s been badly hit. In October last year 31% of patients in accident and emergency departments waited longer than four hours before being treated, discharged, or admitted to hospital, against a target of 5%. And 28% of patients waiting for a diagnostic appointment waited longer than six weeks, against a target of 1% (fig 3).3 In November ambulance response times for life threatening incidents stood at 9 minutes and 26 seconds on average, against a 7 minute target,4 and 22% of patients with an urgent referral for suspected cancer were waiting more than two weeks to see a specialist, against a 7% target.5

Percentage waiting longer than six weeks for a diagnostic appointment (NHS in England)3

It seems that no part of the NHS is immune. While waiting times have been exacerbated by covid-19, they have been rising for many years. So, have long waits become a chronic condition, or can the NHS do what it did in the first decade of the century and reduce excessive waiting?

The task for the NHS, as before, is likely to be immense, with no quick fixes. Sajid Javid (England’s secretary of state for health and social care until last July, three ministers ago) conceded last February that waiting lists would worsen and would start to come down only in 2024.6 Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies that modelled future elective waiting lists supports this view.7 The institute projects that total lists will increase to a peak of between 7.4 million and 10.8 million over the next year, with a central scenario peak of 8.7 million.

The NHS has had some success tackling very long elective waits: the number of patients waiting more than 18 months has fallen from a peak of 123 969 in September 2021 to 46 157 by October 2022, for example.1 But the fact that 2.9 million elective care patients are still waiting longer than 18 weeks and that monthly activity has not recovered to the levels immediately before the covid pandemic underlines the scale of the task.

Missing from all the routine waiting times statistics is the sense of the effect that waiting has on patients. Reducing waits in accident and emergency, for example, has saved lives. As researchers from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, Cornell University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found, as a result of the four hour accident and emergency target around 15 000 lives were saved in 2012-13 alone. The corollary, of course, is that longer waits mean that avoidable deaths increase.8 Compared with the 69% of accident and emergency patients who last October waited less than four hours (fig 4), in 2012-13 around 95% of patients did so.9

Percentage waiting longer than four hours in accident and emergency before discharge home, treatment, or admission (NHS in England)9

History suggests that we have a choice as to whether excessive waiting becomes a chronic condition, but treatment will require effort, resources, and commitment.

“We’ve done this, we can do it again”—learnings from the reduction of waiting times in the noughties

Tom Moberly, UK Editor, The BMJ

From 2000 to 2010 the introduction of a wide range of focused initiatives led to a sharp decline in waiting times for elective care in the NHS. The average wait for inpatient treatment fell from over 13 weeks in 1997 to 4.5 weeks in 2009.10 The experience of the people involved in that work, and those who have studied it, informed a recent King’s Fund report on strategies to reduce elective care waiting times now.11

At the report’s launch Paul Corrigan, a special adviser on health to the former Labour government, pointed out that the government initially had to make the case for why long waits mattered before it went about developing policies to tackle them.12 “Although these reforms are looked at as sets of policies, what actually they were, as far as the government was concerned, were sets of arguments,” he said. “You really needed time to persuade both the NHS and the wider public that these things would work and that they mattered.

“The best argument that had to be had was that long waits mattered; the NHS saw them as simply part of the world. It took a solid year of row after row after row to say, ‘This matters.’ It took a year, but now there are very few people in the NHS who say long waits don’t matter.”

It then took the best part of a decade to make substantial progress on reducing waiting times, Corrigan said, but the initial, incremental progress was important in showing people that improvements could be made. He said, “Every long march starts from the short step, and that short step can be experienced by a frontline member of staff as a big breakthrough.

“We were facing an NHS that fundamentally believed long waits were there for ever and always have been, and that was it. Actually, just getting some of that movement had a dramatic impact and got momentum.”

That initial momentum, together with the knowledge that there was a long term plan to support the work, gave people optimism that they could deliver the changes required—that it was “doable, rather than it’s all impossible,” Corrigan said. “It does involve a 10 year plan, because that’s hope,” he said. “It’s how we motivate and applaud that motivation and celebrate that motivation at a time of extreme despair.

“That’s not easy, but I think it’s incredibly doable. It’s how we turn a moment of despair into a moment of hope and say, ‘We’ve done this, we can do it again.’”

Also speaking at the launch of the report, Nicola Blythe, a researcher in the policy team at the health think tank the King’s Fund, said it was clear from the interviews she did for the report that those involved in delivering the 2000-10 reduction in waiting times had recognised the need to develop the workforce. “What we’re talking about is . . . investment in people, a recognition that people would be the means to the end of 18 week waits: having enough of them but also ensuring that those people feel supported and valued to be able to work towards that very ambitious ask time,” she said.

“It was striking to me, at least in the interviews we did with these experts, particularly those who were closer to central policy making at the time in the Treasury, that when we asked questions about cost effectiveness and value for money the responses were quite surprising, in that that wasn’t the question necessarily posed to them at the time,” she said. “There was an acceptance that achieving an 18 week target would require additional resources and people. The question put to them was less how can you make the case for the money for this, [it] was how are you going to resource this effectively, and have you spoken to the workforce directorate within the Department of Health about how this is going to be resourced and achieved.”

Footnotes

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.